On September 7, 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered a speech in Kazakhstan titled, “Promote Friendship Between Our People and Work Together to Build a Bright Future”, in which he proposed jointly creating a “Silk Road Economic Belt”.1 The Silk Road Economic Belt, which encompasses political, economic, trade and cultural elements, calls for enhanced communication in five areas: policy coordination, road connectivity, unimpeded trade, money circulation and mutual understanding between the various peoples. As a component of China’s strategy of expanding its openingup westward, the development of such a Silk Road Economic Belt would provide China and other countries involved with greater regional cooperation opportunities.

Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) countries not only form a cooperative market, they also play a role in linking the European and Asian markets and help promote cooperation between the European Union and China. The rapidly growing cooperation between China and Central and Eastern Europe is expected to facilitate the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt. A detailed and objective assessment of the role Central and Eastern Europe will play in facilitating the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt between China and Europe is of realistic significance.

Feasibility of CEE’s Involvement

China and many CEE countries were already conducting cooperation in various fields, which has laid a realistic and practical foundation for the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt. CEE countries would benefit economically from a Silk Road Economic Belt if they would tap their market potential and geographic advantages.

Market Potential and Geographic Advantages

Firstly, the CEE economies are representative of transitional economies and have diverse economic development modes. The countries are making the transition from being emerging economies to developed economies, and will thus benefit from financing from China, which in turn constitutes a testing ground for Chinese enterprises looking to invest in the European Union. Enjoying relatively good investment conditions such as cheap and abundant labor, the CEE economies can help China access the EU market and EU technology more easily. Because of this, Chinese investment in the region has increased in recent years with multi-tiered cooperation and exchanges taking shape, this will pave the way for a Silk Road Economic Belt that can stretches to the EU.

The majority of CEE countries enjoy good relations with China, with neither salient historical conflicts nor outstanding issues left over from history. So the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt led by China is less likely to meet obvious strategic resistance. Most CEE countries are not only friendly with China; they are also keen to seize the opportunities offered by China’s development. They constitute the key fulcrum for building a Silk Road Economic Belt.

Bilateral Cooperation Relating to Corridor Construction

At present, Eurasia boasts three finished or about-to-be-finished continental land bridges: the Siberian Continental Bridge (also known as the First Eurasian Continental Bridge), starts from Vladivostok in the eastern part of Russia and ends in Rotterdam in the Netherlands; the New Eurasian Continental Bridge (also known as the Second Eurasian Continental Bridge), begins in Lianyungang in east China’s Jiangsu Province and ends in Rotterdam. It exits China via the Alataw Pass and runs through Central Asia into Russia, Poland, and Germany; the third is the Eurasian Continental Bridge that is now on the drawing board. This proposed route would start from Shenzhen in Guangdong Province and end in Europe via Myanmar, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey and Bulgaria.

The Silk Road logistics corridor operated by China mainly uses the Second Eurasian Continental Bridge. In October 2011, the first “Chongqing-Xinjiang-Europe” international freight train made the journey from Chongqing, China, to Duisburg, Germany. In October 2012, the first “Wuhan-Xinjiang-Europe” freight train left Wuhan for Prague, the Czech Republic. In April 2013, Chengdu launched a regular rail freight service between Chengdu and Lodz, Poland, the “Chengdu-Europe Express”. In July 2013, Zhengzhou began to operate freight trains between Zhengzhou and Hamburg, Germany, via the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. Compared with current maritime and air freight transportation, railways are more competitive for some goods — faster than maritime transportation and cheaper than air transportation. On top of that, rail transportation is conducive to changing the overdependence of China’s foreign trade on sea transportation, therefore creating favorable conditions for the diversification of its freight and energy transportation. The operation of these corridors is a good foundation for the construction of a Silk Road logistics corridor linking Asia and Europe.

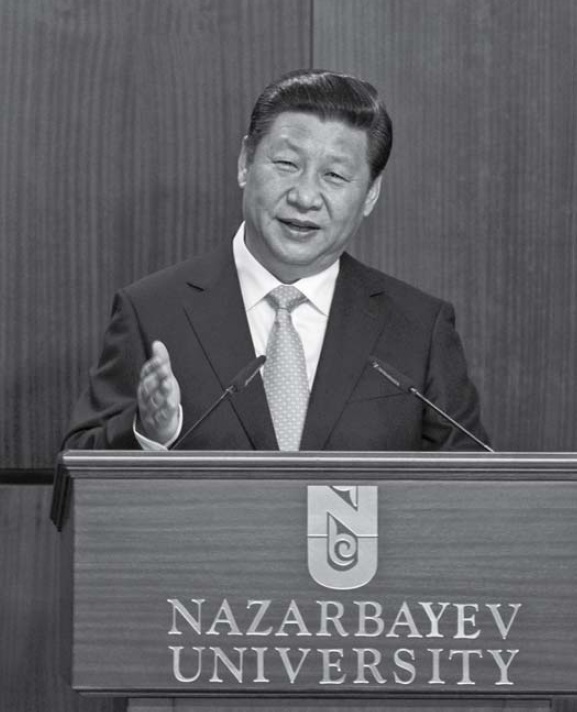

Chinese President Xi Jinping raises the initiative of building the Silk Road economic belt at the Nazarbayev University, September 7, 2013.

Diversified Cooperative Mechanisms

Today, the mechanisms for the involvement of Central and Eastern Europe in a Silk Road Economic Belt are varied. The most important mechanisms to be capitalized on are the cooperative mechanisms between China and CEE countries, the cooperative mechanisms between China and the EU, and the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM). Among them, as far as the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt is concerned, the cooperative mechanisms between China and CEE countries are the key.

The “looking east” of CEE countries is intensifying and their wish to acquire more development opportunities from China is evident. CEE countries have unveiled measures aimed at enhancing cooperation with China and they are conducting frequent highranking exchanges. Even countries which previously had problems with China, such as the Czech Republic, are showing signs of improving bilateral relations. Relations between China and CEE countries are showing positive interaction, and Central and Eastern Europe is a new growth point for Sino-European cooperation.

The Silk Road Economic Belt initiative will present many opportunities for CEE countries. Polish think tanks hold that the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt based on the Eurasian Continental Bridge will boost the bilateral cooperation between China and Poland, and bring many opportunities for the country’s development. In 2012, the Polish Government launched the “Go China” project for Polish enterprises, and thereafter, launched the “Go Poland” project for Chinese enterprises with a view to pushing forward bilateral economic, trade and investment cooperation. Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency officials said it was their wish to attract more Chinese enterprises, particularly Chongqing enterprises, to invest in Poland through the “Chongqing-Xinjiang- Europe” railway, as they want Poland to be the bridgehead for Chinese enterprises entering Europe. The railway line from Chengdu to Lodz, Poland, although not free from problems, has already blazed a trail for the bilateral cooperation. Between April 2013 and January 2014, 33 trains arrived in Lodz from Chengdu, with the value of the freight transported reaching US$ 90 million.2

Hungary and Serbia have also shown great interest in joining a Silk Road Economic Belt. Although there are a number of difficulties standing in the way of a rail link between China, Hungary and Serbia, efforts are being made to support the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt in these and other European countries.

Pathway Choice

Spanning Eurasia, a Silk Road Economic Belt would encompass quite a few countries and regions. So the choice of pathways for a modern Silk Road has a direct bearing upon the role of Central and Eastern Europe. At present there seem to be three possible pathways:

Model of “Development in Stages”

The construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt will likely be advanced in stages, with the focus on the countries in China’s neighborhood and Central Asia in the beginning. In accordance with the stipulations of China’s 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-15), among the four major border areas to be opened-up – the west, north, southwest, and cooperation with ASEAN – it is the westward opening-up that is necessary to construct a Silk Road Economic Belt between Asia and Europe. This requires deepening the cooperation between the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region and Central, West and South Asia so as to expedite the construction of a logistics corridor between China and its neighboring states, and bring into play the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. With this the primary focus at present, the role of that CEE countries will play will be left to the next stage to clarify, i.e. when the Silk Road Economic Belt is expanded from Central Asia to Europe. The advancement of this mode is, to certain extent, contingent upon the speed with which China and its neighbors push forward regional cooperation. Consequently, what role the CEE countries will play and when they will start to play that role is still to be determined.

Model of “Corridor Development”

Taking the development of the Central Asian corridor as the key initial stage for constructing a Silk Road Economic Belt and pushing it on forward, it is essential that earnest efforts are made to build a Eurasian Silk Road logistics corridor to link up the two big markets of Asia and Europe in an effective fashion.

Chinese leaders have stated on many occasions that infrastructure is the key to the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt, while communication is the key to making the necessary breakthroughs. At the Boao Forum for Asia, Premier Li Keqiang said that since infrastructure facilities and mutual communication constitute the prerequisites for development, countries in the region should join hands in stepping up of the development of infrastructure for rail, highway, aviation, and marine transportation.3

Should the three Eurasian Continental Bridges be firmly established then the majority of CEE countries will be incorporated into the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt. It should also be noted that the CEE countries could also have a role to play in the construction of the 21st Maritime Silk Road, which China has also proposed. One of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road routes goes from Guangdong to Greece, and reaches the heartland of Europe via the Balkan Peninsula. This route would save seven to ten days compared with the traditional silk road.

Model of “Equal Development Between the East and the West”

The development of a Silk Road Economic Belt linking Asia and Europe would necessarily strengthen ties between the countries in the middle. Presently, China’s economic and trade cooperation with both ends of the Eurasian continent is flourishing.

On the Asian end, the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area was launched in 2010; China, Japan and South Korea began negotiations on an FTA in November 2012; while Xinjiang and other areas are pushing for FTAs with Central Asian countries.

On the European end, China is showing interest in bilateral investment and FTA negotiations. To date, China has signed FTA agreements with Switzerland and Iceland and is now in talks with the EU over a bilateral investment accord. Compared to the cooperation at either end of the proposed Silk Road Economic Belt, China’s plans of building FTAs with countries such as Russia, Ukraine and Belarus are not clear. However, as the Eurasian Economic Union involving Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan is to be established in 2015, FTA construction and interaction along Silk Road Economic Belt should be active and brisk. Considering the growing economic and trade relations between China and Russia, it can be expected that the two countries could make breakthroughs in constructing an FTA and this is worth exploring in a positive way.

To execute the model of “Equal Development between the East and the West”, Central and Eastern Europe has an important role to play. Firstly, CEE countries are located either on the periphery of the EU or in the center of the EU, some boast key ports, and others are overland hubs. CEE countries serve as a gateway to Europe from Asia, which is the reason why China has to count on them to help it forge economic and trade cooperation with the whole of Europe. Second, in the course of China’s negotiations with the EU over the bilateral investment accord as well as the building of an FTA, CEE countries, which have open markets, are expected to be the driving force in pushing forward the talks between China and Europe. Third, Central and Eastern Europe could serve as a center for Chinese products’ upgrading and marketing. The production, distribution, marketing and branding of Chinese products could be first localized in Central and Eastern Europe before being fully Europeanized. In this sense, CEE markets are at the forefront of Chinese investment and construction of a China-EU FTA.

By and large, the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt will hinge not only on the strategic planning by China and its promotion by China, but also on the prevailing international situation and the support and response of the other countries involved. The most likely possibility is that it will be a combination of many models, with its focus varying with the strategic priorities of the different parties.

Challenges Ahead

Constructing a logistics corridor, without a doubt, constitutes a key stage for both China and Central and Eastern Europe. This corridor is progressing relatively smoothly, but it is not without challenges.

Domestic Factors

Due to the fast growth in trade between China and Europe in recent years, China has launched international rail links to West Europe via Central and Eastern Europe: the Second Eurasian Continental Bridge, that links four Chinese cities with Europe via Xinjinag – Chongqing, Chengdu, Wuhan, Zhengzhou – as well as Jiangsu and Shaanxi Provinces. Of these the “Chongqing-Xinjiang-Europe” line has been operating the longest, and it has created a number of new logistics models. However, the shortage of goods on the return journeys leads to spikes in transportation costs and there are still a number of challenges to overcome in China.

First, unhealthy competition has emanated from China’s domestic logistics transportation mismanagement. To survive the competition, the various localities rely on the local governments to interfere in the market. Many provinces in central and western China have taken measures to subsidize their respective logistics corridors to Europe. Although this is understandable, the excessively low prices offered by some provinces have seriously compromised the environment for fair competition and increased the subsidy burden on local governments concerned.

Second, since the various provinces have failed to unite they are competing against each other on price. And since the transportation in China has yet to be optimized to reduce the time and cost, the foreign partners have no motivation to raise their efficiency and reduce their prices. The extra cost resulting from the foreign side, however, is borne by the Chinese side.

Third, there exists the phenomenon of goods transportation moving away from the law of the market. Given the growing specialization of the logistics industry, what kinds of products are transported by air, or rail or sea should be decided by market forces. For example, cell phones, which are small in size and light in weight with high prices, are suitable for air transportation. Laptop computers, which are bigger than cell phones and weigh more, are suitable for rail transportation. Large products big with low overall prices, such as televisions, are better suited to being transported by sea.

However, some goods transportation does not observe the market rules, which results in goods accommodating logistics. As the majority of trains from Europe to China have no goods to transport on their return journeys, it is usual for the empty containers to be sent back to China via sea transportation, which is a waste of both resources and capital.

External Factors

The prominent external factors are the intensifying scramble for the Eurasian transport corridor and the dilemma of choice for China in establishing its Eurasian corridor.

Given the huge potential of the Eurasian market, states and regional organizations have unveiled their own plans for constructing such a corridor, one after another. To date, the United Nations, the United States, the EU, Russia, Turkey, Kazakhstan, and Japan, among others, have all announced plans spanning Eurasia, making the contest for the Eurasian international corridor all the more fierce.

The Silk Road is the name used for the various Eurasian trade and cultural communication routes that existed for over 2,000 years. In more recent times, with the development of Eurasian maritime trade and the discovery of the Americas these routes gradually became less important. But the logistics needs of some countries have prompted initiatives for a modern Silk Road.

After the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the renaissance of the Silk Road gathered momentum. In 1998, the International Road Transport Union put forward a plan to reopen a Silk Road. The UN then played a big role and launched the first and second projects of the Silk Road Regional Program in 2000 and 2005. UNESCO and UNESCAP also released their own plans. In 1995, the EU, based on the UN plan, launched a plan for a transportation corridor linking Europe, the Black Sea, the Caucasus, Caspian Sea, and Central Asia. Research was mainly funded by the EU, with sponsors such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the Islamic Development Bank, etc. The plan skirted Russia and strengthened the connection between the EU and Central Asia.

Russia’s idea for a modern Silk Road finds expression in the Eurasian Economic Union. On November 18, 2011, the presidents of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan signed an agreement that will bring about the establishment of the union in 2015, stressing that communication infrastructure and a corridor for transportation convenience should be the prime targets of cooperation.

The prominent external factors are the intensifying scramble for the Eurasian transport corridor and the dilemma of choice for China in establishing its Eurasian corridor.

In July 2011, then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton introduced the US’ “New Silk Road” plan in India while attending the Second USIndia Strategic Dialogue. The US plan is a comprehensive strategy that includes Afghanistan, Central Asia and South Asia. Its implementation requires constructing a trade and energy corridor linking Europe, the Indian Subcontinent and South Asia. In so doing, the United Sates intends to dominate the development process of South Asia, Central Asia and even West Asia, and maintain and intensify its influence in these regions in the hope of overshadowing the influence of Russia and China.

Underlying all these different Silk Road initiatives is the geopolitical rivalry among China, the EU, Russia and the US for energy and resources. Russia and the EU are the two big players in Europe, Russia hopes to maintain its grip over the former members of the Soviet Union in a bid to control the gigantic bonanza of business opportunities generated by the Eurasian logistics corridor, while the EU harbors the ambition of reducing Russian influence and ridding the logistics corridor of Russian risks so as to ensure an easy and effective trade conduit between Europe and Asia, and explore more avenues to ensure its energy security.

Although the United States has no historical links with the Silk Road, its strategy in West Asia and Central Asia has much to do with a modern Silk Road. And the United States has been following big corridors in the region and it is supporting the approach of the European Union The contest between the European Union and Russia over the construction of the Eurasian corridor has brought no little amount of trouble, and China must take into account this complicated rivalry in advancing its own plan for a Silk Road Economic Belt.

China’s Eurasian corridor is naturally dependent on the good momentum in Sino-Russian relations and is vulnerable to the intervention of other powers. Russia has been concerned that China’s Silk Road Economic Belt will pose a threat to it, and it has been exerting pressure on China over the choice of logistics corridors. Russia wants the Silk Road Economic Belt transportation corridor to be the northern route, using its Siberian railways, while China prefers to take the shorter southern route. There have always been concerns in Russia and some European countries over China’s attempts to control Central Asian energy resources, and because of this the “China Threat theory” keeps popping up.

The security situation in Eurasia is complex and the strategic and resources competition among powers is exceedingly tense. The political instabilities in region tend to have a negative impact on both the existing and proposed logistics corridors. With the crisis in Ukraine, the United States and Russia have intensified their rivalry, which has increased the risks in this area. Affected by the Ukrainian crisis, China’s plan to invest in a deep water port in Crimea has almost evaporated and the earlier Ukrainian Logistics Center project by China is in flux.

As far as logistics corridors from China to Central and Eastern Europe are concerned, the various supporting infrastructure facilities in the CEE countries are rather underdeveloped and they lack unified standards. Also the double track rate and electrification of the railway lines are much lower than in developed countries. This has impeded progress in China-CEE freight transportation, storage and handling.

Policy Recommendations

To overcome all these problems, the principle of tackling easy issues first and seeking gradual improvement should be pursued. While stepping up its strategic layout for a transportation corridor, the Chinese Government should fully respect the law of the market, stress the leading role of enterprises and allow key projects to be the driving force. The emphasis should be on the avoidance of economic and political risks and on doing what can be done.

The existing mechanisms should be fully used and new communication channels tapped so as to deepen cooperation. It is important that China make a full use of the China-CEE Economic and Trade Forum as well as regular meetings between local leaders from China and CEE countries in a bid to promote wide-ranging communication and multi-tiered cooperation. Multilateral communication platforms should be established to facilitate exchanges of people and investment, and to expand bilateral cooperation on various levels, including state, provincial and municipal levels, and direct and specific collaboration between industrial zones. Meanwhile, research funds should be put to good use to step up research on relevant topics.

It is also necessary to inject new life into the ASEM mechanism. The ASEM has been in operation for many years, and it can be an important cooperation platform for the Silk Road Economic Belt, as it serves as a point-to-point communication platform between China and the EU, as well as between China and CEE countries. The ASEM is actually a good choice in pushing forward Silk Road construction, as it is a diversified and flexible platform for communication.

The multiple choices available for logistics corridors should be maintained so as to ensure the smoothness of trade. On the one hand, cooperation with Russia should be insisted on.

It is supposed for China to be actively involved in the layout of European infrastructure construction to strengthen the connectivity of roads. And the railways in the CEE countries are in need of upgrading and restructuring, as well as electrification, which provides China with a good opportunity to “go abroad” and a good basis for facilitating the construction of a Silk Road Economic Belt in Central and Eastern Europe. As the rail network in Central and Eastern Europe is mainly within the framework of pan-European railways, it is essential China avoid conflicting with the EU when entering CEE countries. Extra care should be given to choice and design of projects.

Mutual benefit and win-win results should be the guiding principles, stressing the positive significance of a Silk Road Economic Belt to the two big markets of Asia and Europe. A Silk Road Economic Belt that includes China, Russia and Europe would benefit all three. China should make clear to Russia and the EU that its Silk Road is an economic concept that would be beneficial to both of them.

Liu Zuokui is an associate research fellow at the Institute of European Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

1 Xi Jinping, “Promote Friendship Between Our People and Work Together to Build a Bright Future”, Astana, September 7, 2013, http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/zyjh_665391/t1078088.shtml.

2 Tomasz Jurczyk, “V4-China Trade: A Polish Perspective,” presented at the Visegrad International Conference “China-V4 Trade and Investment Cooperation: Trends and Prospects”, Bratislava, April 22, 2013.

3 Li Keqiang, “Jointly Open-up New Vistas for Asia’s Development”, speech delivered at the Opening Plenary of the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference on April 10, 2014, www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/boao2014/2014-04/10/content_17425429.htm.